Articles

SMH Op-ed: I’ve spent my life fighting nuclear. Here’s what Dutton isn’t telling you about his reactors

Today’s voter has it tough, especially younger Australians who get much of their information from apps. It’s daunting to sort fact from fiction in the Wild West world of online media, where hidden agendas and speculative opinion are rife. All the more so when a party’s policy only truly makes sense if viewed through a wider lens.

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton’s promise to build seven small-scale nuclear reactors, ostensibly to help meet future energy needs while keeping carbon emissions at bay, therefore needs to be seen for what it really is: a staggeringly bad idea, a stunt and a con. It is a backdoor attempt to pander to the fossil-fuel lobby – and under the electoral spotlight, more people will figure that out.

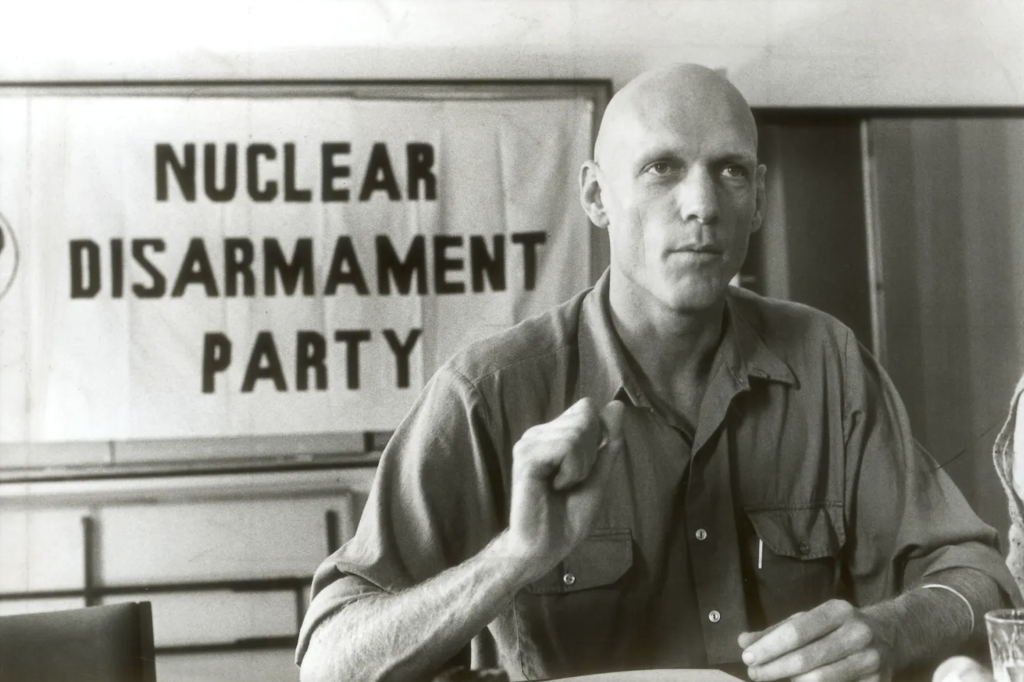

Younger voters understandably won’t know that a generation their age once packed the Sidney Myer Music Bowl with Midnight Oil, INXS and other friends to “Stop the Drop”. They won’t remember our Nuclear Disarmament Party campaign, which won Senate seats in Western Australia and NSW in the ’80s. They can’t know what it was like to grow up during the Cold War era or live through horrific meltdowns at the Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear power plants, which were also “completely safe” until the day that they weren’t. But generations Y and Z can still smell a rotten idea when they give it a good sniff.

At first blush, nuclear energy is causing less concern to younger voters, who haven’t yet taken a closer look. When they do, they will find that most experts and qualified observers view the proposal as expensive, difficult to implement, prone to significant uncertainty and full of rubbery figures.

One example is the fanciful assumption that nuclear plants could be built in 12 years. Twenty years would be more likely – if they are built at all. Cost overruns and safety issues are equally certain. And the carbon consequences of prolonging our old coal-fired power generators are dire.

This deceptive proposal has all the Trumpian hallmarks: a quasi policy announcement intended to serve sectional interests – in this case, fossil-fuel conglomerates – while simultaneously serving up a cartoon enemy as ideological whipping boy, namely renewable energy.

Australia has abundant sunlight, plenty of wind, plus lots of pumped hydro resources that can all be converted by increasingly efficient technologies. Stored batteries are ramping up, too. The butterfly has emerged from the chrysalis and taken to the skies – the renewable energy transition is well under way. Construction costs will keep coming down. Supply will keep going up. The future is already here.

By wrenching the country off this course, Dutton’s plan would leave old, dirty, coal-fired power stations staggering on at increasing risk of breakdown, putting off the day of reckoning when we finally stop polluting and heating our world and get on with using affordable, reliable energy that does not cause more climate chaos.

Peter Garrett at a Nuclear Disarmament Party press conference in 1984.Credit:Ruth Maddison

Peter Garrett at a Nuclear Disarmament Party press conference in 1984.Credit:Ruth Maddison

The trend line is unarguable: renewable energy is cleaner, greener and getting cheaper every year. It will supersede fossil fuels in the blink of an evolutionary eye. Nuclear is a last-gasp delaying tactic.

Over 4 million Australian homes and businesses have solar panels on their roofs. South Australia routinely produces 75 per cent and sometimes up to 100 per cent of its power from renewables and is racing towards net zero, with the other states in hot pursuit. Most electricity added to global supply comes from clean energy.

When the Climate Change Authority, headed by former NSW Liberal government treasurer Matt Kean, released a report showing Dutton’s policy would result in a 2 billion-tonne blowout in dirty emissions, the Coalition’s response was to play the man and not the ball, and threaten Kean.

When a group of eminent former defence chiefs raised the spectre of nuclear plants scattered across the country vulnerable to the risk of terrorism and accidents, the Coalition response was virtual silence.

When farmers, scientists and community groups questioned the impact on precious groundwater of thirsty nuclear reactors running 24/7, the Coalition response was a shrug.

Compare this with Dutton’s proud promise that if elected, within 50 days he would approve the massive Browse Basin gas development in WA.

Due to its size, the Browse project is known as a “carbon bomb”, given it will release more than 4 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide and blow Australia’s modest greenhouse emissions targets to smithereens.

In these circumstances, the Coalition promise of boosting fossil fuels with “boutique” nuclear reactors coming on stream at some mythical future date to satisfy energy needs and reduce costs is an utter chimera.

It is best understood as a delaying tactic, an Aussie version of US President Donald Trump’s “drill baby drill”, buying more time for multinational carbon producers to keep making super profits and heating the planet at our expense.

And there is another effect of the policy: it buttresses claims that Australia should become a site for the storage of large quantities of radioactive nuclear waste generated by other countries.

Periodically, there are calls for Australia’s outback, with its stable geology and low population density, to be the site for disposal of the world’s radioactive waste. It’s an idea that has been rejected before, but don’t expect it to go away soon.

Recently, a senior US official chided Australia for not being sufficiently enthusiastic about uranium mining. In the transactional Trumpworld we now inhabit, new AI facilities envisaged by Amazon, Meta, Google and the like are expected to draw vast amounts of power, often touted as coming from nuclear.

Given the US still doesn’t have a licensed, permanent nuclear waste site after 50 years of furious debate and unsuccessful political negotiation, storage and disposal of new streams of radioactive waste will be crucial.

If the US president can posit buying Greenland and incorporating Canada as the 51st state, impose tariffs on America’s trading partners at will, and promise to end the war in Ukraine in a day, who is to say earmarking Australia as an international nuclear waste dump is a fanciful scenario? Can anyone imagine “Temu Trump” saying no?

As for polls showing younger Australians are less concerned about nuclear energy … not so fast. I’m confident that equipped with relevant facts, and mindful of the scale of the climate crisis they have inherited, they’ll see Dutton’s nuclear con job in a whole new light by the time we get to polling day.

Peter Garrett is a former Labor minister for the environment and a member of Midnight Oil.

The Green List: Peter Garrett on the ‘high- risk’, ‘cruel joke’ of nuclear energy (The Australian)

The Midnight Oil frontman, former politician and environmentalist says the idea that Australia needs a more expensive and riskier technology when it has an abundance of sun, wind and flowing water is also a cruel joke.

ANDREW MCMILLEN – The Australian

Andrew McMillen talks with the Midnight Oil frontman, former politician and committed environmentalist Peter Garrett about his passion for Australia to turn away from fossil fuels and towards a cleaner, greener, more sustainable future.

Have you always been “green”, or sustainability-inclined?

If growing up in nature and caring about the natural world means being green, then yes. As a young boy, I spent a lot of time playing in the bush. My parents gave me the great gift of freedom to roam, to explore and to imagine. Those experiences still sustain me. As a scout, I ventured further afield, learning self-sufficiency and independence. As a surfer, I learned to respect the power of the ocean, and marvel at its productivity.

Can you remember when you began to think about the environment as something worth preserving for future generations?

Swimming through untreated sewage at Manly in the early 1980s was a turning point as it was obviously both dumb and capable of being fixed. Then on tour with the Oils, seeing other parts of Australia, and then the world, where forests were being clear-felled overnight and skies darkened by pollution brought it home that big changes were needed. Science tells us that earth is “firmly on track” to becoming unliveable, yet we continue with business as usual and timid incrementalism.

Do you think we need a reset on national energy policy because of the emerging costs of renewables?

Yes, but not in the way the question implies. Failure to urgently speed away from fossil fuels poses massive risks as rising emissions turbocharge climate change; witness the growing number of climate disasters making news. The mounting costs of dealing with extreme weather, the health effects of an overheating planet, and impending large-scale population movement are far, far greater than the adjustment costs of moving to 100 per cent renewables and using batteries for storage, which is doable and urgently needed.

The idea that Australia needs a far more expensive, high-risk, difficult to manage and uninsurable technology when it has an abundance of sun, wind and flowing water is a cruel joke. Despite assertions by vested interests, nuclear can’t happen quickly, efficiently or safely enough to deal with the need to get out of oil, coal and gas and put ourselves on a safe, reliable and affordable energy footing. Given the millions of solar panels on roofs and the now substantial contribution of renewables to providing power, I’d say we’re ready. Still, it’s a desperate race to avoid more climate tipping points. Expanding fossil-fuel production flies in the face of rational thinking. It’s time we called it criminal behaviour, since we can foresee the terrible harm being caused.

Is climate amelioration created by individual actions – such as recycling – or government policy? Or both?

Government policy is the key, at every level, local to global. Every step someone takes shifts the dial, too – as does positive action from business. But given the scale of the challenge, only resolute governments can save the day. Governments pass laws and regulations; they design budgets; they can preference industries that don’t ramp up global heating. Tragically, with fracking heading to the Kimberley, and coal and gas being expanded, we’re still waiting.

With regard to your own journey, on green/sustainability matters, do you feel you can accomplish more outside politics?

I can’t judge accomplishment. I felt the same inside as I do now. I mourn the loss of opportunity to get on top of the climate crisis earlier – it’s too real and getting worse. I’m going to keep on with it because the world is surely worth looking after. Are we going to leave a burning mess behind for the next generations to have to deal with? Not if we act resolutely, in whatever way we peacefully can.

Peter Garrett performing with Midnight Oil on January 25, 2022 in Launceston at Mona Foma festival. Picture: Philip Brown

If you had a magic wand, what’s one thing you would change about how we, as a nation, approach our allocation of natural resources?

That we adopt the “do no harm” principle in regulation, so any resources allocation – particularly coal, oil and gas exploitation that increases the amount of CO2, or damages the environment – be ruled out. The employment gains of moving away from fossil fuels are tangible. In many cases, markets have already made the call, yet perversely, fossil fuel companies who pay little tax in Australia and are hellbent on continuing with their destructive business model are still allowed to operate. In summary: start by getting rid of fossil fuel subsidies so energy businesses can operate on a level playing field.

What is your greatest hope with regard to Australia’s natural environment?

That we stop treating the environment as an afterthought. I sense and hope for an attitudinal sea change – informed by Indigenous experience, inspired by our holidays, our artists, our farmers, our gardeners – that lifts our gaze to the extraordinary coastline, reefs, rivers and wetlands, verdant rainforests; the whole panoply of environments to which we owe our existence, and decide irrespective of age, political persuasion or station, that protection of nature – whose health is vital to our survival – is no longer a mercenary trade-off, but as inviolable as family, barbecues and footy.

Far-right forces threaten progress for Indigenous peoples in Australia and Aotearoa

Originally published in the NZ Listener.

From the very first time I visited New Zealand, as it was then called, on Midnight Oil’s first, exhaustive tour of Aotearoa’s towns and cities some 40 years ago, the omnipresence of Maori culture was palpable albeit still peripheral to the casual eye.

This was in stark contrast to the situation across the ditch, where Australia’s Indigenous peoples were then rarely sighted, other than on the sporting field.

Fast forward to today and in both countries much has changed: Indigenous issues are mainstream, the contribution of Indigenous people is substantial.

To the regular visitor from Australia the ‘land of the long white cloud’ is notable as a place where Maori stand at the core of the nation; central to to it’s identity, prominent in sport, politics, arts and community and clearly referenced in language and the cultural expression of the successful, tolerant nation that New Zealand is widely acknowledged to be.

For many Australians, including the six million who voted in favour of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament last year, there has been an uncomfortable awareness that in comparison, the progress of recognition and support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – with the indices of health and well being significantly below the national average – has been painfully slow.

It is true that for Maori and Pacifika there remains similar gaps, and that this situation ought to be successfully bridged.

Yet in your country, partly due to the existence of a treaty between the original occupants and the British crown who attempted to take control, you are further down the track towards embedding Indigenous rights and aspirations.

Add to this the absence of states within a federation – anyone watched our State of Origin rugby league competition recently? – which renders national initiatives easier to implement, and the impediments to political progress are not as great in NZ as in Australia.

In the recent unsuccessful referendum on the Voice in Australia the far flung states of Queensland and WA were significantly opposed. And the politics of localism, alongside the emergence of a dishonest, far right social media push financed by business elites, likely played a role in the failure of the proposal.

This is not to excuse the obvious lack of progress in Australia, and whilst it might not seem apparent for Kiwis when there is now discussion about rolling back some initiatives that support Maori, the analysis above rings still true for me.

Yet, having recently returned from playing a well attended Waitangi Day concert in Auckland, where there was much contention around the issue of Maori rights, and reflecting on the failure of the Yes campaign in Australia, notwithstanding the large numbers of people who ticked that Yes box, it seems clear that our joint journey toward a better shared future is in danger of being interrupted by extreme politics, and the utilisation of social media to introduce scare campaigns and racist commentary.

One of the greatest inheritances both nations possess is the relative absence of religious, sectarian or ethnic rivalries imported from the histories of countries in distant lands.

Indeed many people flee ‘trouble spots’, as they are called, to start new, peaceful lives in peace on the basis that the commitment to equality and opportunity, free of rancour and stigmatising is genuinely held down under.

What a tragedy it would be if in both countries we allowed those voices of envy and stereotyping to drown out the calmer voices wanting to continue our joint forward movement toward greater equity and national harmony.

May reason, compassion and clear headed conversations guide our path. And may we continue to value and promote Indigenous

culture and aspirations that so fundamentally embodies our national identities.

The voice contains hope. It will help end the great Australian silence – Peter Garrett (The Guardian)

We are on the brink of a unique moment when Australians get to make a collective decision. Will we recognise Indigenous Australians in our constitution and heed their simple request for a consultative voice to parliament? The shape and consequences of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity are clear.

Modern Australia came into being as a direct consequence of the casual, often deliberate, destruction of a people’s entire world, notwithstanding efforts by some social reformers of the day. As many understand, this is baked into our soul.

CLICK HERE to read the full op-ed in The Guardian.

AUKUS STINKS, AND THAT’S AN UNDERSTATEMENT

At the very least, ratifying an undertaking of this magnitude should have been subject to thorough scrutiny and debate through all levels of the Australian Labor Party, and in the public realm.

Instead the original announcement, made in secret by three national leaders, two of whom have already left office, has now been given effect by a Labor government.

As stated previously I do not share the benign view of China advanced this week by former Prime Minister Keating. Neither do I wish to impugn my former colleagues who face difficult decisions as they deal with an increasingly unstable region.

Still this is a marked departure from at least half a century of foreign policy leadership in which the ALP has prioritized engagement with our neighbours over the outdated ‘Big Powers’ approach typically favoured by those who prefer the rear view mirror to the windscreen.

To be clear, Australia will now be the only ‘non nuclear’ nation that is in possession of nuclear submarines.

This raises a series of critical questions in relation to the nuclear non proliferation regime, and the management and disposal of nuclear waste.

AUKUS will produce increasing volumes of high level radioactive waste and this, along with the rotting radioactive submarine hulks (if they ever get built), must be safely disposed of and stored for tens of thousands of years in the Australian environment.

Our policy failure over decades with low and intermediate level waste gives no confidence in the future handling of far worse high level material.

God help future generations, especially if they happen to live in the outback or near an existing – or future – defence facility, or if they consume primary products impacted by radioactive leaks into land or water.

Has this cost been factored into the $368 billion price tag? A figure that will inevitably skyrocket in the years to come.

Where were the scientific reports, assessments, and risk analyses that should precede and inform a decision of this size?

Has Defence ever delivered a major construction or weapons delivery program on time and on budget? Not once in living memory.

Ask any Australian how they would spend this amount of public money to make Australia a fairer, safer, kinder nation and I doubt the answer would be nuclear subs.

As many experts have noted, expecting three nations to effectively co-ordinate and deliver a project of this magnitude and over such a long time period is epic wishful thinking, and flies in the face any relevant past experience.

In one stroke this decision has placed in jeopardy Australia’s previous hard won non-nuclear policies and treaty commitments, including the Nuclear Non Proliferation Treaty and the Treaty of Rarotonga.

At the least Australia should now join nearly 100 other countries and sign the new UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, as promised by Labor in opposition.

It is fanciful to make assurances, however genuine, about any aspect of this deal in relation to existing treaty obligations given that the current administration cannot bind future governments.

The main cheerleaders of AUKUS include the Liberal/National Coalition, who’ve never contemplated anything nuclear they didn’t want to embrace without qualification, and the nuclear industry who see this as a gateway to avoid what they have never earned: social license and community trust.

The fact that the leader of the opposition Mr Dutton, would countenance cutting today’s social welfare programs to ensure nuke subs start prowling the coastlines of other countries decades hence says it all.

Magically an attendant local nuclear industry is meant to somehow appear overnight. But there are no prizes for guessing where the expertise and fees will be sourced from – the US – all subsidised by the taxpayer.

There are prudent alternatives for conventional submarines that can fulfil an appropriate defence role at a time of increasing assertive behaviour by China, without any of the attendant risks to our environment and to the treaties we depend on to help avoid a nuclear apocalypse.

If the aim is to better prepare Australia against future potential threats then significant resources for cyber security and the development of a highly mobile, land based defence force, should be considered.

Alongside belt and braces protection for energy, water and communications systems, and accelerating climate mitigation measures.

AUKUS stank when it was stealthily revealed in the dying days of the former government. It still stinks. This unprecedented commitment deserves proper consideration and debate, not just a rubber stamp.

For now we are doing the time warp again. A vassal state is set to become a nuclear vessel state.

The most expensive undertaking in our history stumbles into the future learning nothing from the experience and mistakes of the past. Astronomic costs, wide ranging risks and hostage to the interests and capacities of others.

Peter Garrett: Politicians have the power but not passion to address climate change – The West Australian (op-ed)

For humanity to survive, we must make Australia’s politicians feel our fear and rage Peter Garrett and Paul Gilding

There are no climate deniers any more. Whatever anger we feel at the opportunities missed, we still celebrate that the battle of ideas, at least, is won.

Now there are climate hawks and climate doves. Hawks see a global emergency and the need to mobilise as if human civilisation is at stake. Doves – the moderates in the business community and governments who serve their interests – see a serious environmental problem that we should address, but slowly and without too much disruption, especially to them.

While we welcome the “all aboard the climate train” phenomena, we view the rhetoric and support for action over time, and as late as 2050, as disingenuous at best and fatal at worst.

The government must take responsibility for the Great Barrier Reef and stop looking for someone else to blame

Originally published by The Guardian

Escaping responsibility has become the recurrent theme of the Morrison government. Whether it is the glacial progress of the vaccination rollout, dealing with the megafires two summers ago, or the parlous state of the Great Barrier Reef, someone else is always to blame.

When Unesco released its recommendation to the World Heritage Committee in June to place the Great Barrier Reef on the “in danger” list, the first reaction of the federal government was to blame China.

China is the chair of this year’s committee meeting and given its standing in the international arena, “how good” was it for the government to use Chinese influence as a straw man. Planting a conspiracy theory with a willing media accomplice is too easy, and sure enough, the Australian broke the story with a headline shouting “China-led ‘ambush’ on the health of the Great Barrier Reef”.

This unsubstantiated claim of Chinese plotting – and Unesco’s response that no country was involved in recommendations to the World Heritage Committee – was swiftly followed by claims of procedural unfairness. The government then alleged it was “blindsided” and “stunned” by Unesco’s decision. The prime minister Scott Morrison called Unesco’s processes “appalling”. Unesco repudiated these criticisms too.

The UN body followed proper process used over many years. It never shares recommendations to the committee with any country. Imagine if it did? The lobbying behind the scenes, outside any public scrutiny to weaken draft decisions, would be intense. Notably Australia never complains about this process when it agrees with a recommendation.

The government’s spin doctors then shifted the narrative to the shakier ground of climate, with the environment minister Sussan Ley claiming the reef is being used as a political football and that it needed global action on climate change to ensure its protection. Coming from a government that has politicised climate change for more than a decade, and was recently ranked at the bottom of the ladder for action on the climate crisis, this was as laughable as it was damaging to our international credentials.

Shifting blame on to international organisations is typically the last card played by governments unhappy with the assessment of peers and desperate to deflect scrutiny of domestic policy. Australia’s attempt to use climate as a debating point to cover its policy shortfall was clumsy, and flew in the face of our key allies and trading partners’ commitments to emissions reductions that are far greater than ours.

For most of its 44-year existence, the committee has accepted the sound technical advice of Unesco and its natural heritage advisory body, the IUCN. But it is the case that in recent years the committee – a group of 21 countries – sometimes shied away from making tough decisions that put conservation and protection first. On occasion draft decisions have been weakened and action delayed.

When Australia joined the World Heritage Committee , the head of our delegation said the trend for setting aside sound technical advice was undermining the credibility of the world heritage convention and that “as custodians of the convention, the committee can and must do better”. He promised Australia “will be an advocate for upholding the technical integrity of the committee. We will place great weight on the analysis and advice of the advisory bodies”.

Australia had it right then but how hollow these words ring now when one of our own sites is being considered for the “in danger” list and the Coalition furiously scrambles to weaken the recommendation. In this case the government has form.

In 2014, Greg Hunt, then the environment minister, launched a successful diplomatic lobbying effort to try to convince committee members not to place the Great Barrier Reef on the “in danger” list. Australia managed to avoid the in-danger listing of the reef three times from 2012 to 2014, as evidence accumulated of the deterioration of one of the world’s greatest natural wonders. Each time the committee gave the Australian government one more chance.

In 2015, a long-term sustainability plan to ensure the survival of the reef was unveiled and the committee finally welcomed Australia’s efforts to protect our global icon.

Now in 2021, after three severe coral bleaching events fuelled by global heating and very slow progress in meeting the water quality targets promised to the committee, another diplomatic assault is in full swing. This is the most egregious aspect of the current controversy, other than the escalating risk to the reef.

During the period of Japan’s so-called “scientific” whaling in the Antarctic – which Australia strenuously opposed – I appreciated how focused diplomatic effort can make a significant difference in international campaigns. But these are exceptional exercises that should be conducted with a genuine national and international interest at their core.

With the reef, to deflect the inadequacy of our domestic policies, we will expend substantial financial resources to rescue the government’s reputation, with Ley heading off on a week-long junket overseas and senior bureaucrats diverted from serious work.

It won’t have escaped anyone’s notice that in rejecting Unesco’s advice, the Morrison government is conveniently ignoring that much of it is based on technical and scientific reports produced by the Australian government, with the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority downgrading the outlook for the reef from “poor” to “very poor” in 2019. This advice has been coming for a decade.

Listing the site as “in danger” is an opportunity for the Australian government to unite with the rest of the world to fight climate change and to protect the outstanding universal value of the reef.

Instead, the government is fighting Unesco. Surely we can and must do better.

Fossil Fuel Fixation

‘The balance sheet is breaking up the sky.’

Originally published in Tanya Plibersek’s book Upturn

When the COVID-19 pandemic reached Australian shores, we were on the cusp of a new age. Turbo-charged by a hotter climate, massive bushfires had just scoured the land, confirming what scientists have long maintained, namely, that this continent is especially vulnerable to global heating.

Countless Australians were touched by the catastrophe, directly or indirectly. Homes, farms and livelihoods were destroyed in a season of hell. Some tragically lost their lives, and the toll would have been higher were it not for the monumental effort from firefighters and government agencies. Over a billion native species perished, billions more were displaced, some teetering towards extinction. As palls of smoke, like scenes from a disaster movie, draped cities already running short of drinking water, the climate crisis was literally in our backyard.

The speed, reach and intensity of the fires happened on the back of a one-degree rise in average temperatures. We are currently on track for a rise of three degrees or more by the end of the century.1

For many of us, it is unthinkable that parts of the country could be unliveable in the future, but Aboriginal people in Central Australia, who have occupied the land for longer than can be imagined, are already contemplating that prospect. If we fail to act decisively, a three- to four-degree increase will accelerate environmental decline and push our political, security and social systems to breakpoint. So can we make the change?

The discovery during the COVID-19 pandemic that we could see vast swathes of stars in less polluted skies, hear, the sweet sound of birdsong and see more clearly the immediate natural environment, were some reminders of what we are losing. That is the healthy waterways, oceans and forests, fertile landscapes, all the plant and animal species, and our thoughtful relationship with these that underpin life on earth.

The mantra that any pro-environment decision is a dangerous trade-off between the economy and nature, between ‘jobs and trees’, is still taken at face value in the halls of power and in many newsrooms. Yet there is no economic evidence for this view and plenty of evidence against it. What the evidence tells us is this:

- With imagination, good policies, competent planning and strong laws, we can have plentiful jobs and a healthy environment. There is no better example than renewable energy, the use of which is now accelerating at a rapid rate worldwide.

- With the increasing severity of human-induced climate change, it is the pursuit of profits and maintenance of employment in fossil-fuel-intensive industries that now directly threatens Australian lives and livelihoods.

Look no further than how Australia treats the Great Barrier Reef, recognised as one of the great natural wonders of the world. The coal industry contributes to the global heating now damaging the reef, with three mass-bleaching events in the past five years,2 but in Queensland employs half as many people as work on and around the reef.3 Additionally, this natural treasure generates over $6 billion in tourism each year,4 and is worth over $60 billion to the economy.5 The figures speak for themselves.

There have been periods in modern Australia, usually when reformist Labor governments were in power at the federal and state level, where major environmental challenges were addressed. Australia was instrumental in safeguarding the Antarctic. In the latter period of the last century, there were extensive additions to the national estate, including World Heritage areas like Kakadu National Park and the North Queensland Wet Tropics.

The pioneering Landcare program, along with concerted community efforts to oppose destructive practices and rehabilitate damaged landscapes, show our values.

Yet federal and state governments have never consistently treated the environment with the seriousness it deserves.

Now Australia is a world leader in extinctions – a shameful state of indifference – with native animal species declining at warp speed unabated since 1788, polluted inland river systems run dry, and with hotter, drier landscapes, fire has destroyed large swathes of the country, including areas that never previously burned.

The default position in government is short-sighted; to build or allow anything to be exploited that, it is claimed, will create jobs, without considering the alternatives, or the consequences.

Finally, after a sustained period of economic growth, the endpoint has been reached as Australia’s natural environment degrades rapidly, whilst we continue to spew carbon dioxide and devour resources at an unsustainable rate.

Environment NGOs, citizen scientists, communities and experts have been ringing the warning bell on this state of affairs, but few in our political institutions have listened. Even for those who seek to act, it remains the case that without national leadership we are stymied.

What’s needed is a change of heart and mind in how we see and interact with our world, especially in the political and corporate world where much power resides. Many Australians yearn for politics that will create a robust national framework of policies that prioritises the protection of the environment; attacks waste and pollution; and supports climate-friendly industries and practices.

It is no surprise that the preponderance of donations to political parties from big business generally, and the resources sector specifically, has coincided with the absence of serious climate policy on the part of the Liberal/National coalition. No surprise either that this corporate largesse has occurred in tandem with declining public confidence in the political system. The science is unambiguous. To survive the climate crisis, we have less than a decade to start reigning in greenhouse pollution including reaching net zero emissions by 2050. Consequently, the decisions of the Morrison Coalition, as Australia emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic facing a recession, are as crucial as any contemplated since the Second World War.

To fail to seize the moment means condemning successive generations to a hotter, more degraded, less productive world. If we fail, these generations will judge today’s leaders harshly. For all the talk of ‘a fresh start’, even before COVID-19, a pattern had emerged. The Prime Minister, having appointed a former fossil-fuel executive as his chief of staff, repeatedly downplayed the role of climate change in the bushfires. Talk of establishing any meaningful long-term emission targets was a no-go-zone, and in international climate talks, Australia continued pushing to exploit a historic loophole to meet our current inadequate targets.

This shouldn’t really surprise anyone given the Coalition’s past decades of inaction, and regular defenestration of climate measures once in government. Former Prime Minister John How ard’s recent admission that he never really believed in climate change is instructive. His government’s last-minute foray into an emissions trading scheme was taken seriously by the media and the public, but never by Howard.

The first genuine attempt to get to grips with climate came during the Rudd/Gillard years, where briefly there was a price on carbon, and a raft of policies introduced to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. History records that in a hallelujah moment emissions actually came down. When wrecker-in-chief Tony Abbott became Opposition leader, and then Prime Minister, the sacking of Canberra by the anti-climate vandals resumed and the nation has been stranded ever since. Abbott and Howard, like many conservative politicians, simply do not believe what a substantial body of science, and personal observation, tells us about a heating world.

The country has been held hostage by these unreconstructed ideological fantasists for too long. Yet the Prime Minister and numerous Liberal/National members are cut from the same cloth. The implacable hostility to protecting the environment and addressing the climate crisis remains hard-wired into the DNA of conservative politics. How else to explain the multiple cuts to the Environment Department since the Coalition took office in 2013, to the extent it can no longer perform its functions properly? How else to explain the continuing hostility to renewables, despite the coalition now tacitly accepting Labor’s Renewable Energy Target (RET), which it previously attacked mercilessly? The RET has worked so well that wind and solar are now unequivocally cheaper and cleaner forms of energy than coal- and gas-fired power. The world is moving forward, seeing the lower costs and new jobs as an opportunity. We are missing that boat.

How else to explain the drive to reform national environmental laws under the guise of reducing so-called ‘green tape’, announced before the recent bushfires? As they stand, the laws to protect nature don’t work effectively and can be easily circumvented by a determined government. The expression ‘green tape’, pushed incessantly by the resources sector, is simply code for freeing up rigorous approval procedures. In any event, Coalition ministers have rarely used their powers to rule out actions that may cause damage to matters of national environmental significance.

How else to explain the convening of a secret review led by a leading fossil-fuel executive, Grant King, to provide advice on reducing energy prices? The conclusion? Australia’s funding agencies for clean, renewable energy should now invest in fossil fuels, something banks and investors are baulking at. In the age of so-called fake news, this was fake policy development.

Since the pandemic began, the Prime Minister has urged a return to ‘business as usual’, with a ‘laser-like focus on jobs. The COVID-19 Commission, again led by a resources sector CEO, Andrew Liveris, is championing a gas-fired recovery, whereby potential major gas projects could be subsidised with taxpayer funds. Another form of industrial socialism aimed at turning the world into a blazing inferno.

The release of Energy Minster Angus Taylor’s Energy Roadmap with the buzz phrase ‘technology not taxes’, followed. Whilst cobbling together a range of potential measures to reduce emissions, the roadmap effectively replaces Australia’s long-term targets to reduce carbon emissions altogether. Instead, it highlights gas (again), previously intended as a transition fuel, which would lead to increased emissions and require support from taxpayers to be economical.

Other suggestions included a wink to nuclear power – unproven, unsafe, and expensive – with additional investment for carbon capture and storage technologies which to date have failed to deliver. The Coalition’s supposed free-market principles are jettisoned for their ideological obsession.

Side note: The roadmap also includes pumped hydro with an emphasis on ‘Snowy 2.0’, which aims to effectively act like a giant battery connected to the existing Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme. Snowy 2.0 is extremely expensive and unlikely to fulfil the claims made by former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull. Small-scale pumped hydro projects would be much more effective. Much of the roadmap is ‘profoundly irrational’, as one analyst put it, aimed mainly at protecting the revenue stream of the country’s most emission-intensive assets.

Next came the interim review of national environment laws by senior businessman Graeme Samuel, which, to no-one’s surprise, found they were ‘not fit to address current or future environmental challenges’.

Overnight the government ruled out a key recommendation for an office of independent oversight, whilst cherry-picking the proposals for greater deregulation, which suited its agenda despite no compelling evidence that this initiative was likely to lead to better environmental protection.

In a rush to open the floodgates to unregulated developments, the environment minister announced the government would legislate on this issue prior to the release of the final report and before public comments had been received. The die was cast.

Scientists and experts have repeatedly pointed out what is necessary to avert disaster, as they did with COVID-19. That is setting ambitious short- and long-term targets and reducing greenhouse gas emissions immediately and at scale.

Meanwhile, the world – and the global markets on which we depend – is moving on and will soon leave us behind. The mainstream is embracing the obvious, asking ‘if we have to rebuild the economy, why rebuild it dirty and risky?’

As the Economist argued earlier this year, the COVID-19 crisis ‘creates a unique chance to enact government policies that steer the economy away from carbon’. They pointed out that ‘Getting economies in medically induced comas back on their feet is a circumstance tailor-made for investment in climate-friendly infrastructure that boosts growth and creates new jobs. Low-interest rates make the bill smaller than ever’.6

The World Bank7 and the International Monetary Fund8 are calling for equivalent policy shifts. The European Union is seizing the moment to stimulate economic activity by directly funding climate action. Germany is creating ‘future proof jobs’, in areas specifically aimed at reducing carbon emissions. At home, the Morrison Government delivered a poorly designed tradies’ bonus, without linking the package to improving energy efficiency, and so reducing energy costs, or even addressing social housing shortages.

As Treasurer, Scott Morrison famously hugged a lump of coal in parliament, and there is no sign this love affair is waning, despite the economics of coal heading south. The world’s largest fund manager, Blackrock, is abandoning companies with major investments in thermal coal. Insurers are retreating from coal operations and it won’t be long before investors assess Australian government bonds through a climate lens. Then we will really be in strife. There are conflicting views across the parliament, with some members in thrall to an imaginary future where a dirty, dangerous and increasingly uneconomic source of energy prevails over cleaner and cheaper alternatives. Many MPs refuse to acknowledge we are facing a climate emergency, preferring to delay the day of reckoning with a range of responses; ranging from outright denial to band-aid incrementalism. Yet the necessity for a safer, more stable future path has never been clearer.

It sees us becoming an energy superpower, ably described by Professor Ross Garnaut in another chapter of this book. Here abundant solar, wind and precious rare mineral resources are deployed to meet current energy needs at a lower cost whilst exporting surplus energy to the regions.

This approach guarantees growing employment, with professional services network Ernst & Young’s most recent finding that a renewables-led recovery would produce almost three times as many jobs as one based on fossil fuels.9 We could build a new manufacturing base, reduce our dependence on imports (from China in particular), and adopt technologies that get us to zero emissions as soon as possible.

Finally, we could again play a constructive role in the global community effort to stabilise the Earth’s climate after years of spoiling and undermining genuine attempts, like the Paris Agreement, to build an international consensus on reducing plan et-heating emissions.

Australia’s relative success in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic was based on an essential three-way compact: governments working together in the national interest, incorporating the advice of scientific experts, underpinned by community co-operation.

The threat of a pandemic was immediate and required drastic action. However, the threat the climate crisis presents is of far greater magnitude, albeit unfolding over a longer time frame.

The Economist again:

COVID-19 has demonstrated that the foundations of prosperity are precarious. Disasters long talked about, and long ignored, can come upon you with no warning, turning life inside out and shaking all that seemed stable.

The harm from climate change will be slower than the pandemic but more massive and longer-lasting. If there is a moment for leaders to show bravery in heading off that disaster, this is it. They will never have a more attentive audience.

This is clearly no longer business as usual. Our future health and prosperity depends on a healthy planet. Seize the moment we must.

Peter Garrett

Peter Garrett AM is a musician, activist and former Labor member of federal parliament. He is a renowned environmentalist and social justice campaigner through his work with trailblazing rock band Midnight Oil and his decade as Australian Conservation Foundation President. He was a Cabinet Minister in the Rudd and Gillard Governments and was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Australian National University.

Garrett

- ‘Addressing global warming’, Climate Action Tracker website, December 2019, <climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/>.

- Graham Readfearn and Adam Morton, ‘Great Barrier Reef suffers third mass coral bleaching event in five years’, the Guardian, 25 March 2020, <www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/25/great-barrier-reef-suffers-third-mass-coral-bleaching-event-in-five-years>.

- ‘Explained: Adani’s continuously changing jobs figures’, the Australia Institute, Medium, 26 April 2019, <medium.com/@TheAustraliaInstitute/explained-

adanis-continuously-changing-jobs-figures-e2a67baac540>. - Deloitte Access Economics, At what price? The economic, social and icon value of the Great Barrier Reef, 2017, <www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/ Documents/Economics/deloitte-au-economics-great-barrier-reef-230617.pdf>.

- Deloitte Access Economics, 2017.

- ‘Countries should seize the moment to flatten the climate curve’, the Economist, 21 May 2020, <www.economist.com/leaders/2020/05/21/countries-should-seize-the-moment-to-flatten-the-climate-curve>.

- ‘Climate change’, the World Bank website, 2020, <www.worldbank.org/en/ topic/climatechange>.

- ‘Climate mitigation’, International Monetary Fund website, 16 October 2019, <www.imf.org/en/Topics/Environment/climate-mitigation>.

- Michael Slezak, More jobs in renewable-led COVID-19 economic recovery, EY report finds, ABC News, 7 June 2020, <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-07/

renewable-led-covid-19-recovery-will-create-more-jobs-ey-report/12322104.

What I learnt in a revelatory journey into the desert

It starts with lullabies, the most elemental of musical offerings. Then nursery rhymes, hymns sung in church and school choirs, especially carols. One of my favourites was ‘Out on the plains the brolgas are dancing lifting their wings like warhorses dancing … and the refrain, apart from kangaroo and billabong, likely the first Aboriginal expression I’d ever heard, ‘Orana (welcome) to Christmas day’.

As I was growing up Ella Fitzgerald, Gershwin and Elvis oozed out of the magisterial, grey HMV record player sitting in the corner of our living room. Then came sparkling Brit-pop on the radio with the Beatles, Kinks, Who, and our (sort of) own Bee Gees in full swing. Starting with ‘She Loves You’, ‘You Really Got Me’, ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’, ‘New York Mining Disaster’, and it went on from there.

Later I set out to discover the blues, as all aspiring singers are won’t do. Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, Renee Geyer, Chain. After leaving home and zigzagging through university I tended to bands that reflected the country I knew; Skyhooks, The Dingoes, and later Cold Chisel and Yothu Yindi, the list eventually, thankfully, stretching longer than a full forward’s arms.

Finally, I found musicians that pushed hard, when I met a young Rob and Jim already writing songs with bite, then Martin arrived with a guitar and away we went.

It seems like an ancient history ago now but back then we were just trying to figure how to present the gems we were creating (at least to our ears), and, crucially, our political take on things, to an indifferent world.

In these formative years, I knew by heart the hymns and anthems of my schooldays, including God Save the Queen, minus the Johnny Rotten snarl – all generated from the western canon. The songs that landed in the ears of kids growing up in the 60’s and 70’s – again mostly imports from London or LA – were utterly familiar.

Yet at that time I cannot recall hearing any music of any kind that emanated from Aboriginal Australia. Put it down to a sheltered middle-class upbringing, and the narrow gate through which any sound travelled to the ears of my generation. The ‘great Australian silence’ was deafening.

This expression coined in 1968 by anthropologist WEH Stanner, refers to the unacknowledged history of British colonists taking by force a continent already occupied. Aboriginal people were ‘a melancholy footnote’ Stanner said, and this great Australian silence echoed in the small life of a suburban teenager.

A whispered, widely held sentiment that ‘It was better that the blacks should die, than that they should stain the settlers heath with the blood of his children’, was unfamiliar to me. As for the songs, old or new, of First Nations people, I’d heard nothing.

——

Fast-forward to 2017 after my decade in formal politics whilst the rest of the band played on we’ve come together to find out if being on stage still works for us – it does. Then to see if our audience is still around too – they are. Lucky days.

There’ll be no shortage of new songs if we decide to have a go at making a new album but whether they join the ranks of the hundreds already recorded is an open question. Few bands successfully reunite other than as nostalgia acts, and fewer still produce anything that isn’t a pale imitation of earlier work.

Hence the Makarrata Project, drawing on long time connections with Aboriginal people, collaborating with Indigenous artists, and featuring the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which called for a constitutional recognition for First Nations people, a Voice to Parliament, and a coming together – a Makarrata – to unite.

In 1986 we’d gone out with the Warumpi Band from Papunya on the aptly named Black Fella/White Fella tour, playing to towns and small settlements through remote and northern Australia.

Our immersion in Indigenous culture and non-Europeanized landscapes was brief but revelatory. We discovered what was rarely mentioned at school or university, namely, a vibrant and pervasive culture still extant within the fledgling modern nation we’d grown up in.

If we’d bothered to look we would have encountered Aboriginal people in any town or city, albeit hidden from view. Still the absence of much of the ephemera of city life provided space to think about what had actually happened in the past, and what lay ahead. We were changed forever.

As for music, there was plenty. At the apex were the ceremonial songs and dances that marked important occasions. The hypnotic rhythms of chanted songs, with clapsticks, and sometimes didge, that is increasingly familiar today.

In many settlements there was all kinds of western-influenced stuff: rock, reggae, surf instrumentals, often played on makeshift instruments and run-down equipment as if people’s lives depended on it. Incidentally, nowadays this activity is a given.

In some larger towns country music had preceded us. Slim Dusty, who with his wife Joy Mc Kean spent a lifetime on the road, was a name to reckon with. Battered acoustic guitars were pressed into service to entertain neighbours with the maudlin twang of country classics and originals.

Here was a pub band from Sydney, too loud and too fast for the world we’d entered, performing to some of the so-called “poorest people” in the world according to Encyclopedia Britannica, with the shock of white invasion still reverberating across the red dirt.

Yet we were made welcome, and the sharing of significant law objects by the Pintupi people in the Western desert- a remarkable gesture for its time – was a turning point.

The Warumpis had already toured some of these parts. The legal fiction of Terra Nullius that at that time had sanctioned white settlement because Australia was ‘a land belonging to no-one’ was a joke. Every corner of the country and all that lay between was brimming with people who’d been living there forever – the First Australians – and there was music.

Towards the end of the tour at Numbulwar, a small town on the coast in Eastern Arnhem Land, I lay outside in the night air to listen as the Warumpis loped through a song called My Island Home, written by guitarist Neil Murray and singer George Rrurrambu. The song is a bittersweet yearning of a man wanting to return to his birthplace, Christine Anu later successfully covered the track.

As the music spilled out over an audience of a couple of hundred people sitting under trees outside the public school I was struck, as I have been many times since when listening to First Nations’ artists, by how real the sentiment is, as against much western popular music with its fleeting conceits and extreme narcissism.

Like My Island Home, many of the songs by Aboriginal artists at that time, and since, fix on country and family, the tragic losses and deep longings.

But politics is never far from the surface. The lyrics spelt it out. In Warumpi’s From the Bush, No Fixed Address Bunna Laurie in Coloured Stone … white man’s burden.

Over time we became aware that white Australia did indeed have a black history. It’s incredible that for many years Aboriginal men were excluded from voting whilst being accepted into the army to go and fight for king and country, and that is just one example of many.

The call of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples seeking justice for the theft of their lands and waters, their wages, and tragically in many instances, their children, was growing ever louder.

Fair-minded Aussies were supportive, and a movement for reconciliation emerged, to be embraced half-heartedly by governments. Mining and pastoral interests and sections of the conservative establishment blocked and frustrated change.

The High Court eventually put Terra Nullius to bed, but the abridged form of land ownership called native title that emerged was far from satisfactory.

A Royal Commissions into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in 1986 saw many recommendations ignored. Since then over 400 more deaths have stilled the air.

In the national arena, Bob Hawke promised a treaty in 1988 – nothing. Both sides of politics promised to address the significant social disadvantage suffered by Indigenous Australians-little progress.

During his tenure, John Howard refused to offer a formal apology. Kevin Rudd repaired that omission decades later but no government has managed to seriously to close the gap. Tony Abbot cut half a billion dollars from the budget and abolished the department of Indigenous Affairs, whilst saying ‘lifestyle choices’ of Aboriginal people shouldn’t be subsidized, and then received the highest Queens’s birthday honour for ‘services ‘to the Indigenous community, and Malcolm Turnbull refused to countenance a voice to parliament for Aboriginal people on the grounds that it would constitute a third chamber in the parliament – it wasn’t anything of the kind.

In 2016 Adam Goodes was booed out of the sport he excelled at by braying racist crowds, whilst the AFL and many in the media turned a blind eye.

Last month one of the world’s largest mining companies chose to destroy rock paintings that had been on the walls of Pilbara caves before the Egyptians built the pyramids.

Is it any wonder a Black Lives Matter movement has surged with younger Australians out on the streets?